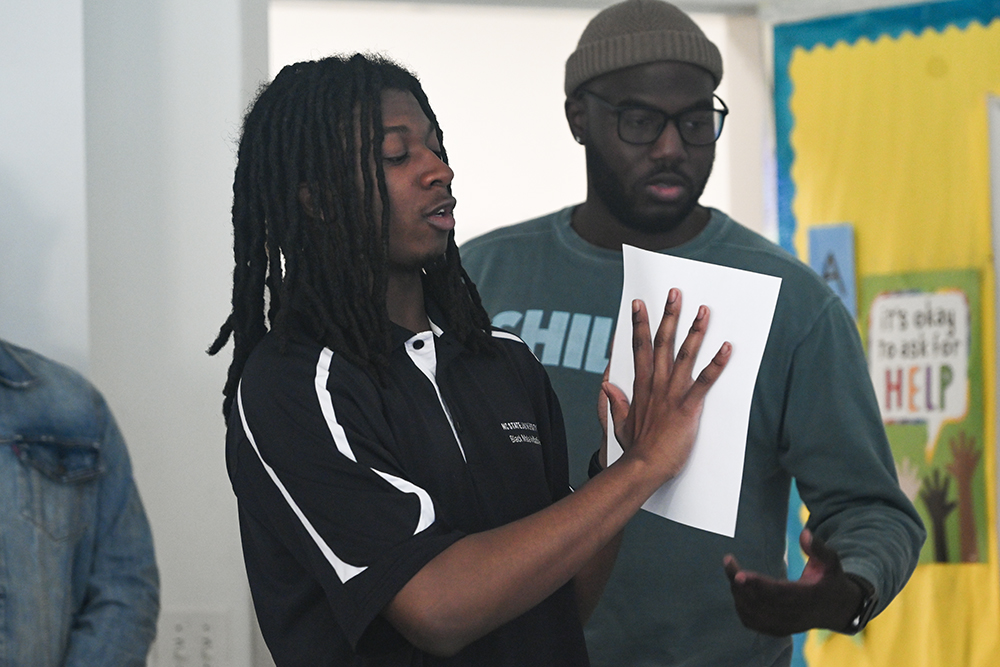

Image by Alexia Alexander

In the heart of historic Charlotte, an enslaved man named Bonaparte operated a barber shop at the Charlotte Hotel. Hired by his owner in the mid-1800s, Bonaparte worked as a barber and even had an advertisement in the newspaper to coincide with it. “With Scissors sharp and Razor keen, I’ll dress your hair and shave you clean.”

After the Civil War, Bonaparte became free and moved to Alabama where he started a family. The story of Bonaparte the Barber, once lost and unnoticed, was studied by Charlotte native and NC State student, Alexia Alexander, who uncovered and mapped out Charlotte’s slave history.

In her senior year of high school, Alexander created a digital map to highlight and commemorate the “places where enslaved men and women lived, worked, were sold, worshiped and lived their lives before the Civil War.” The map titled, “Charlotte’s Lost Slavery History,” earned her a Girl Scout Gold Award with the local Hornets’ Nest Council.

Alexander’s digital map is a powerful tool that provides a visual opportunity to recognize the lives and contributions of enslaved individuals in Charlotte’s history. By pinpointing specific locations tied to slavery, such as homes, businesses and churches, the map brings light to stories that have long been obscured or forgotten.

Nubian Message: What inspired you to create a map of Charlotte’s lost slave history?

Alexia Alexander: At Myers Park High School, I took an African American Studies class and I noticed that there wasn’t any local history. We learned about Frederick Douglass, Marian Anderson and Rosa Parks, but there were no local names. I thought it would be cool to include local history and names from where we live…the enslaved people that made Charlotte what it is today. I feel like they’re important as well and that’s what really motivated me.

Oftentimes, Black history is brushed over with a few prominent names. Schools and teachers typically don’t take the time to teach beyond a set curriculum, resulting in a lack of local history. Alexander’s ambition and compassion led her to begin a journey towards educating people who may be unaware of Charlotte’s local Black history. The connection between Alexander and the history of Charlotte motivated the creation of this significant educational visual.

NM: What was the process for creating the map?

AA: To create the map I got help from a librarian. Her name is Bridget Sanders from UNC Charlotte…I got all my information from newspapers and this website that you go through at the library. They have a census and if you type in a name it gives you all the information about that one person, like maybe dating back to the 1800s or 1700s. So that was pretty cool. In terms of the map being made, I just used Google Maps, and made my own map and implanted those sites.

NM: Who was the most impactful person you learned about?

AA: The most interesting one was Bonaparte the barber for me. He was an enslaved man and he cut hair. He had his own barber shop and I just felt like it was important to me because even though he was an enslaved man, he still did his own thing. That really inspired me.

Another poignant example highlighted by the map is the Grace AME Zion Church, built in 1902 on South Brevard Street in Charlotte. A former enslaved woman named Dorcas Burton donated a striking stained glass window to the church. Burton was determined to enjoy its beauty while still alive after a life of bondage and oppression.

The map also reveals how the labor of enslaved people was deeply woven into the economic success of Charlotte. From the gold mines running beneath Charlotte’s streets, where hundreds toiled in brutal conditions, to the railroad construction projects dependent on enslaved workers, the map traces how this injustice created wealth and infrastructure that still exists today.

NM: As a college student, how do you plan to continue your efforts and what kind of impact do you hope the map will have?

AA: So, I’m an Animal science major. When I did this project, I honestly didn’t think it would be as big as it was. It kind of surprised me and it also made me happy to know the project is long lasting…it’ll be there forever. I can still be in college, and people can go take the tour to learn new things. As far as how far I want it to go, maybe it could get into classrooms…instead of just learning about Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, they can get students to learn more about their hometown. Maybe Myers Park could include my map. I never thought about that but maybe they can include my map in their lessons so kids can learn about lost slavery history.

Although Alexander is now a second-year Animal science major, she hopes her work can find its way into educational curricula so more students learn the neglected history of their hometowns. Making this local connection could inspire deeper engagement with the struggles and achievements of African Americans throughout history. The “Charlotte’s Lost Slavery History” map is a model for how communities everywhere can unearth and share their own vital stories of enslaved peoples.

NM: This month is Black History Month, but Black history is never-ending. How do you think you’ve contributed to Black history by creating this map?

AA: I think I’ve contributed a lot by providing this information that a lot of people didn’t know. My own family didn’t even know and I was able to uncover lost slave history. I feel like I’ve made a big impact, especially in times we live in now. Kids don’t learn much about Black history and I feel this is a good way to spread the word…so more local Black history can be known.

By giving names and locations to those who lived as enslaved people, Alexander’s project helps to restore identity and recognition. Her map makes an indelible statement, ultimately pushing the message that their lives mattered and their stories should be remembered and passed down. The map is a reminder that Black history is indeed never-ending, and hidden in plain sight if we choose to take a look and dig a little deeper.