The Black community has unlimited potential. Yet, we internalize societal stereotypes that limit our capabilities, to measure our intelligence and identity. These societal stereotypes do not just affect how others see us – but how we see each other. It creates divisions that leave Black people uncomfortable in their own community, judged for being “not black enough.” Even a Black person’s so-called “Blackness” is being put on a scale and weighed between whitewashed and culturally Black. Let’s talk about that.

This is a learned divide. Generational systematic oppression has shaped the way the Black community defines itself, and these racist ideologies were never abolished with slavery or washed away after the Civil Rights Movement.

In an article titled, “How Have Social Stereotypes Changed over the Last Century?” published by Kellogg Insight of Northwestern University, says, “‘You can think of some archetypal examples of how our stereotypes of Black Americans have changed over time, from lazy in the 1900s to helpless in the 1990s.” The article continues, “It’s a different word, but it’s got the same meaning of incompetence and negativity.”

These stereotypes still hold ground and have simply transformed into something tolerable for modern society. The division within our community is not accidental —it is the direct consequence of history that weakens us in the name of being “Black.” They persist in our modern struggles: poverty, gentrification, coded racism and more. We as a community can perpetuate them under the strain of further division.

So, it’s time to redefine Black.

The Black community has endured a long, oppressive history. That history has bled into our community values, influencing our speech patterns, career choices, socioeconomic positions and music tastes. That history is the root of our community’s internal divisions, perpetuating friction in the Black community that manifests as colorism, class division and the idea of an “authentically Black” person.

Many stereotypes that Black Americans have internalized trace back to some point in history. During slavery and following its abolishment, federal and state governments systematically withheld education from Black people, contributing to the myth of Black intellectual inferiority.

Despite the barriers, many Black people educated themselves or fought for the Black right to education. Frederick Douglass, for example, taught himself to read and write by making friends with white kids asking them for lessons and reading books in secret during the night.

After slavery, education became a path for advancement within the Black community. However, the Black people who sought education became distanced from the community due to their perceived proximity to whiteness.

Those Black communities’ internalization of the inferiority of Black intelligence led them to believe that the ability to speak “proper” English and excel academically was “acting white.” The same ideology persists today with the Black community – deeming those who speak “proper” or display professionalism as white-washed.

This leads the Black community to fear that evoking their intelligence will invalidate their racial identity, which divides Black populations in schools into Black students who excel and those who do not.

W.E.B DuBois discusses and even advocates for this divide, famously stating, “The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth.”

The Talented Tenth was DuBois’s idea that the top 10% of the Black population—at the time—would be ready to pursue higher education and harness the qualities of leaders to lead the Black population. This ideology of a small portion of Black people carrying the Black race is counterintuitive, as to grow as a community, the community must grow together. This discussion of a Black elitist group divides our community even more, expanding the gap between the wealthy and the poor.

The lack of societal mobility when deprived of education and resources are not unique to the Black community. Collectively, during Industrialization, there was a systematic economic divide between the wealthy and poor due to a small group of people owning all the factories. Enabling the idea of a Black elite group would foster the same economic divide.

The historical tension surrounding Black advancement alters how the modern Black community views successful Black professionals, such as saying they have forgotten where they’ve come from or calling them “bougie” or “white.” Even today, Black people often walk a fine line between their identity and the white professional world, having to balance respectability politics and embracing their identity. Commonly, these professionals are isolated from the Black community for losing touch with their roots, when that is rarely the case.

In turn, more successful Black people judge low-income Black people for “not trying” or “being hood” when, in reality, systematic struggles are the root cause of their struggles. These perceptions within the Black community are counterproductive and distract from historical and systematic causes of poverty.

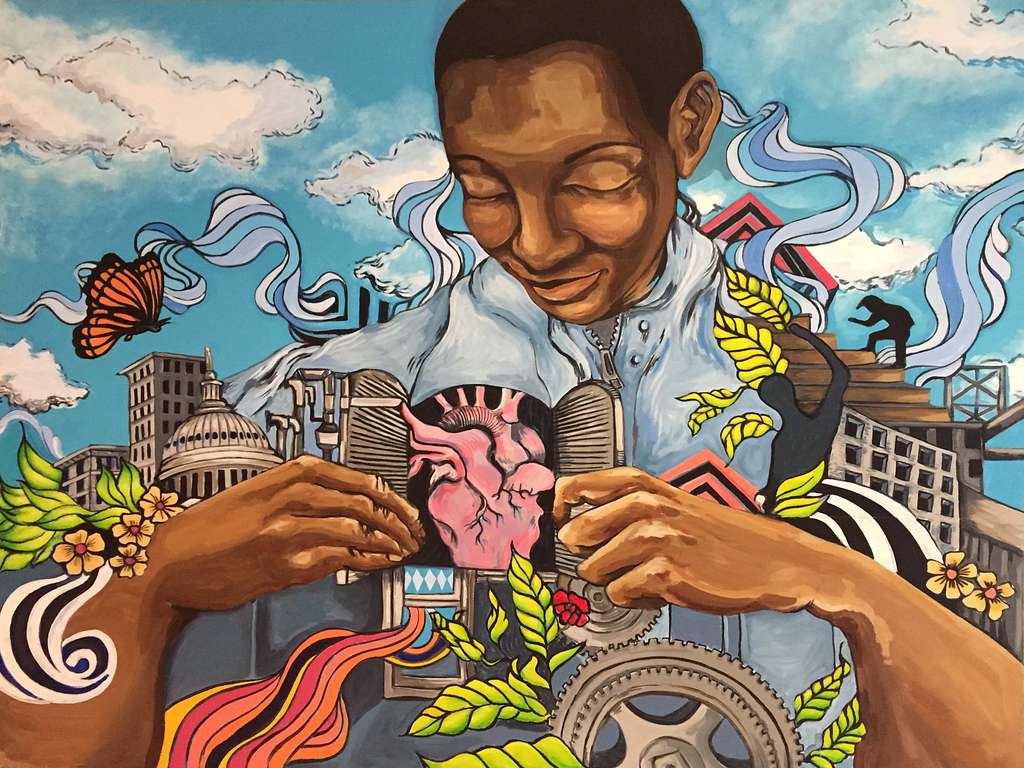

Blackness is not a monolith. Black is not an identity that needs policing. Black is not a single way of speaking, acting or living. Racist historical narratives cannot measure your Blackness. We, as a community, are diverse and talented, and it’s time that we let go of societal labels that contain us.

We must uplift all Black people, including entrepreneurs, scholars, artists and more. To truly celebrate being Black, we must celebrate the full spectrum of the Black identity. Enabling the idea that there is one way to be Black detracts from our culture and creates division. Reinforcing the narrow definitions of Blackness deepens these divides. So, let’s change the narrative and reclaim Blackness without limitations.

Black is a spectrum.