While scrapbooking is a well-known art form, fewer are familiar with zines. Purdue University classifies a zine — a word derived from magazine — as a self-published or DIY booklet.

Zines are accessible forms of expression, regardless of someone’s current skills or quality of materials. All you need to make a zine is a piece of paper, a pen and a message in mind to share.

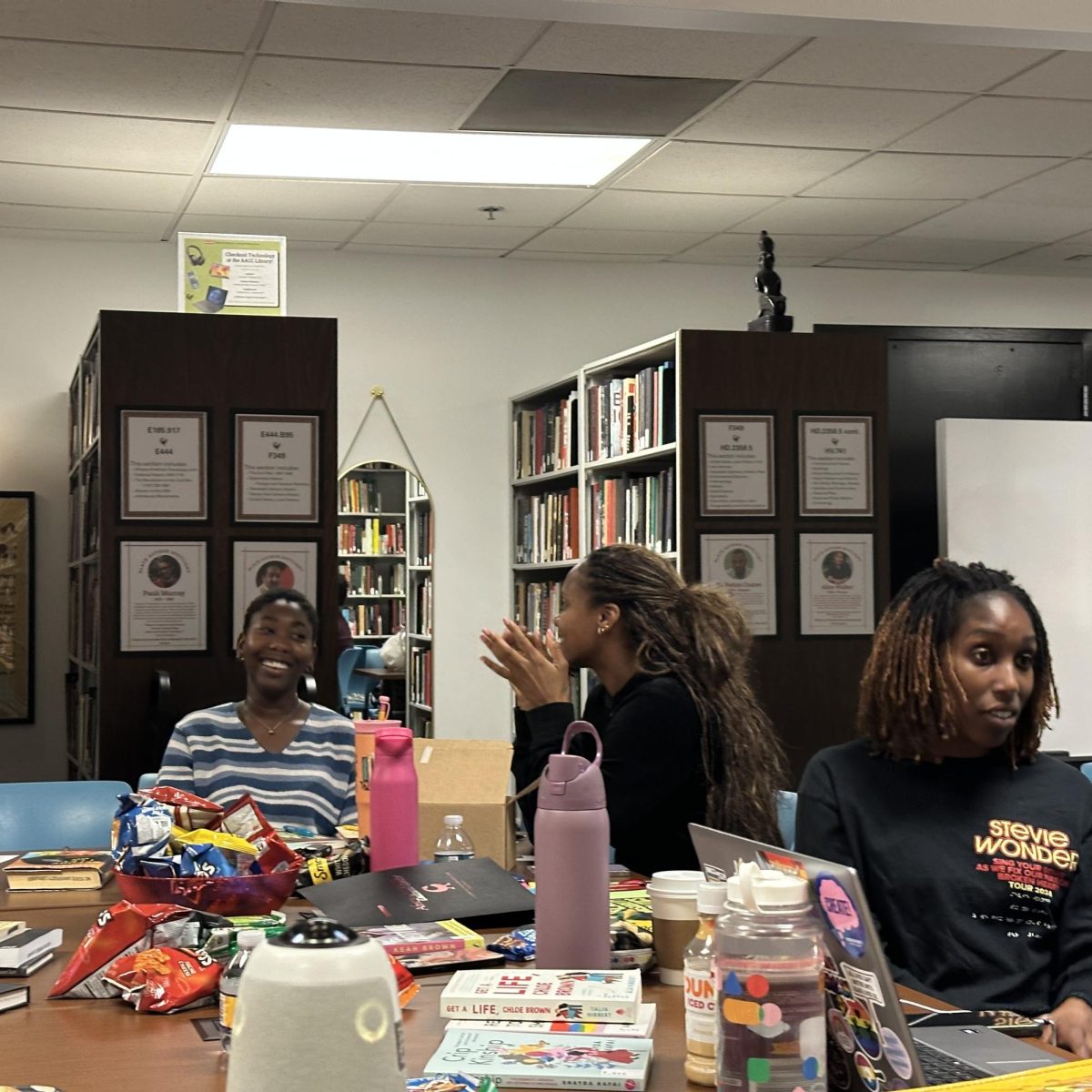

For this reason, zines have deep roots in cultural practices, political activism and womanhood. To dive deeper into the connection between these subjects, the Women’s Center hosted the Womanist History of Scrapbooks and Zines Workshop on March 25.

The Nubian Message interviewed Valeria Perez, who led the workshop. Perez is a fourth-year student studying zoology at NC State who works with the Women’s Center as the creative director of education for The Movement Peer Educators. She hosts a variety of educational workshops on topics including safety and community for women.

Perez explains, “I’m a Puerto Rican student who moved to the U.S. specifically for college. All my life, I had found that a lot of the spaces where I was able to connect with my female family members pertain to crafting, to cooking and traditional women’s crafts, in a machista Latino society like in Puerto Rico.” A machista is someone who believes in male superiority and upholds strict gender roles through an exaggerated idea of masculinity.

While these norms could lead to a feeling of oppression, small communities can be formed in reaction that offer a space to share your experiences freely. Perez further describes, “Historically, in a lot of different cultures, arts and artistic expression has been one of the few things that women have been allowed to have access to — to voice and or represent their identities and experiences.”

Historically, zines have focused on many things. Surrealist “Dada” zines that critiqued the bourgeois were popular in the 1920s, while in the 30s, fun sci-fi zines were big. In the 1950s, Samizdat zines helped communicate the practices of the Soviet government. In the 60s, comic book zines became popular, only to pivot back to politics with punk movements in the 70s. From there, zines continued to intertwine with alternative culture through Riot Grrl zines in the 90s, which concerned politics and feminism. So, with these small pockets of freedom, women have been able to find solace in the creation and sharing of art.

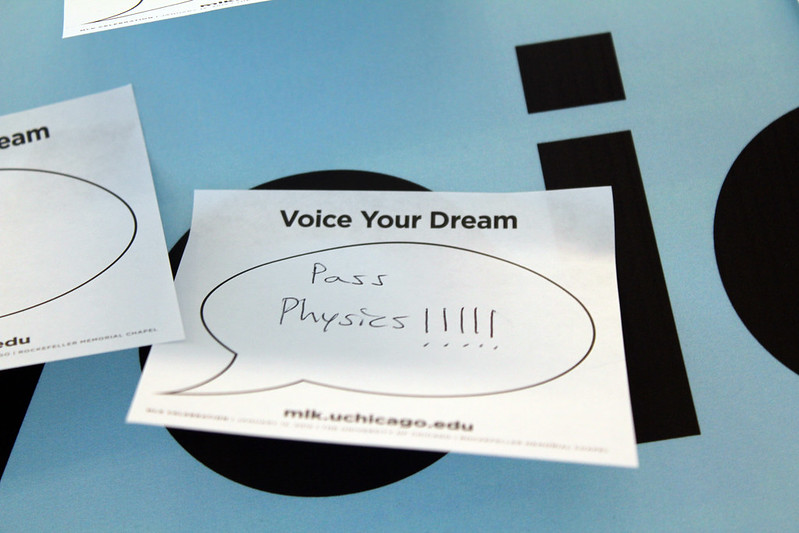

This political activism mixed with artistic expression is a unique part of zines. With the zines’ flexibility, many authors incorporate both of these aspects into their work. Perez explains, “Anyone can make it [zines], anyone can spread it, and they can be very nuanced, complicated and personal. The fact that they’re easily digestible and made to be shared is intrinsic to the spread of activist thought and truth seeking.”

The personal nature of creating art to share is also part of its charm. Perez says, “being able to physically represent [thoughts] and communicate them in an intimate way, in a creative way, in a way that evokes emotion, evokes thought and conversation. I asked in the event, ‘What do you think is a key component of good storytelling?’ And I think being able to provoke thoughts out of somebody, being able to force somebody to connect not only with themselves, but with what they want to know is very, very important right now.”

Perez urges, “We are keeping critical thinking alive, or our art is keeping these movements alive … your words, your art has a space … [There’s] a beautiful legacy of radical art. I don’t want it to be lost on anybody that it’s Black art, and it is Black women’s art. Sometimes that can get lost in online spaces, but it won’t get lost here.”

As a final message, Perez says, “Push yourself to connect with the part of you that longs to create … it’s really important not to understate the importance of providing yourself the opportunity to be able to connect with that creative side and do that in community.”

The NC State Women’s Center has a zine library where students can read local zines and learn more about their history. Why not see what you can create?