Anahsza Jones| Managing Editor

On August 25, 2016 I was privileged enough to get the opportunity to see Memphis at Raleigh Little Theatre, and let me say, I was absolutely blown away. As a veteran Broadway enthusiast, I will admit, I didn’t have the highest expectations. Call it New Yorker’s arrogance, but I just didn’t expect big things from an off-Broadway theater with ‘Little’ in the name. I can’t even stand corrected because this production brought me to my knees.

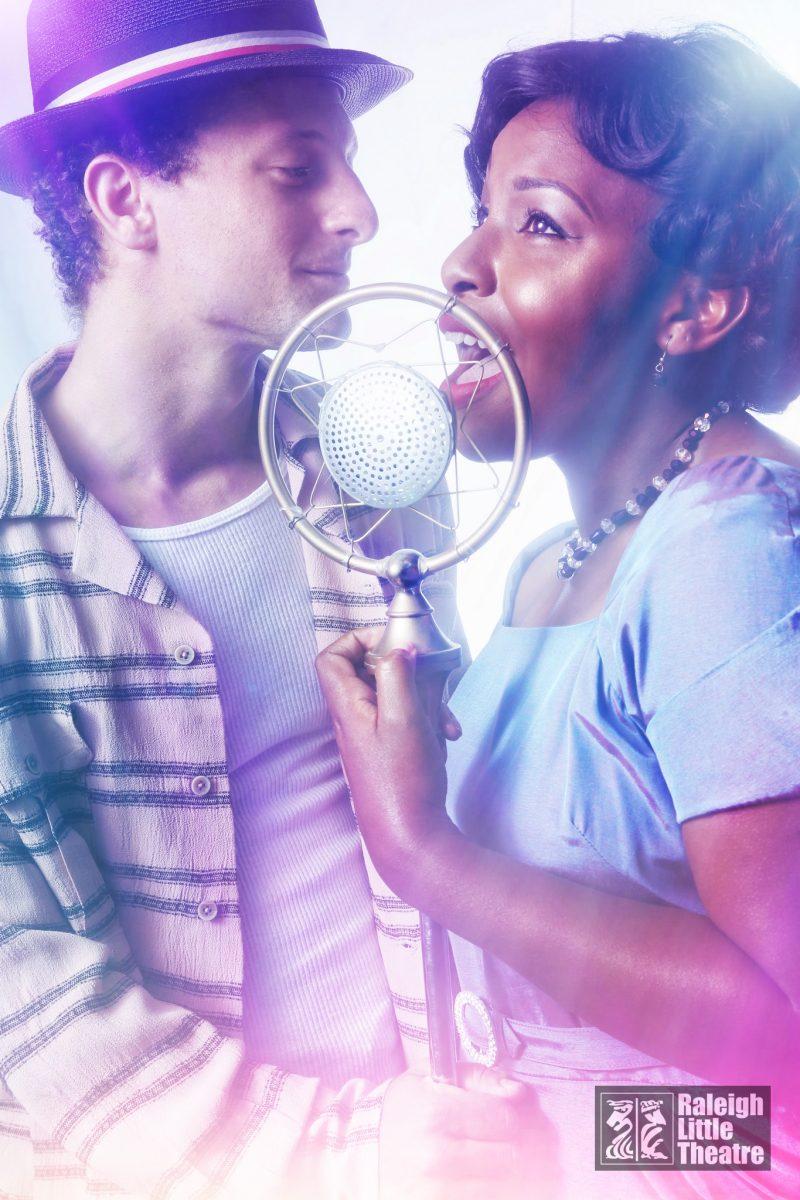

Memphis tells the story of Huey, played by Zak Casca, a white radio personality and his determination to bring black music to the white populace, and Felicia, played by Aya Wallace, a black singer and superstar hopeful. I won’t give too much away, but yes, there is a love interest, and no, it isn’t all sunshine and rainbows. Understand, the story takes place during the 1950’s, not the friendliest time for interracial couples to thrive, and the play underscores that quite clearly.

But this play is about so much more than interracial love. Patrick Torres, artistic director of the Raleigh Little Theatre and director of Memphis, said, “Part of the play is talking about privilege, and a lot of the play is talking about…cultural appropriation. You know, like, whose music is it?”

In the play, Huey introduces black music to the white masses, in effect, taking credit for not only the success of the music, but the music itself. In one song, ‘She’s my sister,’ Felicia’s big brother Delray accuses Huey of stealing the music, and follows with “I don’t blame you, that’s the American way.”

And he has a point. Several, actually. White America does have a history of taking things that doesn’t belong to it, black people, Hawaii, and much of the continental United States to name a few. But this musical particularly focuses on how white America claimed historically black music as their own. Not nearly as many people as should understand that rock and roll was created by black people, just rhythm and blues sped up, according to Felicia.

The topic of the musical begs the question, where does appreciation end and appropriation begin? At least stealing the music is understandable. As one of the songs states, “Everybody wants to be black on a Saturday night.”

And I could not have been happier to be black than I was in that theater. Even though the events of the story are fictional, the environment, the situations and racial climate of the setting, all of that was real. Being a college student at a predominately white institution, I’m constantly reminded of the differences between myself and my peers, but I know I haven’t thought about all the nuances of what it’s always meant to be black in this country.

Randy Jordan, a long time radio host and the actor that plays Buck Wiley said, “This brings a sense of what those times were like for African Americans and people trying to break those barriers. It will give a sense of that heritage and the price that was paid.” I could not agree with him more.

Now for a little bit of background. The character Huey was inspired by Dewey Phillips, the man credited with bringing African American Music to mainstream radio and introducing Elvis to the air, as well as Alan Freed, the man who coined the phrase Rock and Roll and held some of the first integrated concerts.

Jordan said, “Whether they [Radio hosts] knew it or not, playing African American, or black, music, it made a difference… whether they were civil rights pioneers or no, they sure impacted communities and open doors, broke down some barriers.”

Huey’s character, and the situations he initiates really make you wonder about the black artists of the time, shut out from the world they longed to be a part of, that of mainstream music, where they would really be heard. Torres said, “What you never hear is ‘what was the black artist’s reaction to these people playing their music on the radio?’ That is not a narrative that gets told. This play begins to speculate what that would have been like.”

And speculate it did. We get to watch Felicia vacillate between hope, joy, fear and determination throughout the play. Not only her, but also her brother Delray, played by NC State’s own Juan Isler, Event Coordinator of Rave when he isn’t on stage. Delray is the proverbial protective big brother, and a realist to boot. He offers a darker contrast, no pun intended, to Huey’s naïve optimism. He was one of my favorite characters, despite his surly disposition. More than the singing or even his love for his sister, what stood out to me was the hint of anger just below the surface.

The character was such a contrast to Isler himself, who I’d met previously. When asked what he fed off of to make his character come to life, Isler responded, “I turned the T.V. on. I didn’t turn it on to a show from the fifties, I just turned it on.” He went on to liken the attitudes of people in the fifties to the recent incidents of police brutality, and the fear that people of color experience on a daily basis when being confronted with these attitudes and situations. Watching the race relations play out on stage was intriguing yes, but also a bit scary.

This play brought home a reminder that it wasn’t that long ago. There’s a certain familiarity to it because many of us may still hear our grandparents, or great grandparents playing the music of this time. For Randy Jordan it wasn’t even that far removed. He spoke about his upbringing, how, during a trip to New Orleans, he witnessed the blatant, in-your-face racism that was not only common, but expected. “It was cultural, and it was ugly,” said Jordan.

But the ugliness did give him a place to channel from to play a very convincing racist disc jockey.

All of the cast did a beautiful job of channeling from their own experience to bring the story to life, because they had a lot to do with the interpretation of their own characters. Torres made sure there was a level of autonomy for the actors because he is aware that not being black limited him in the scope of understanding the conflicts fully. “I can’t tell them their story,” Torres said. “You can’t tell someone else their truth.”

“Our backgrounds have led us to what Memphis is,” Isler said. “It’s almost in certain ways like we’re not acting. We’re just being ourselves.”

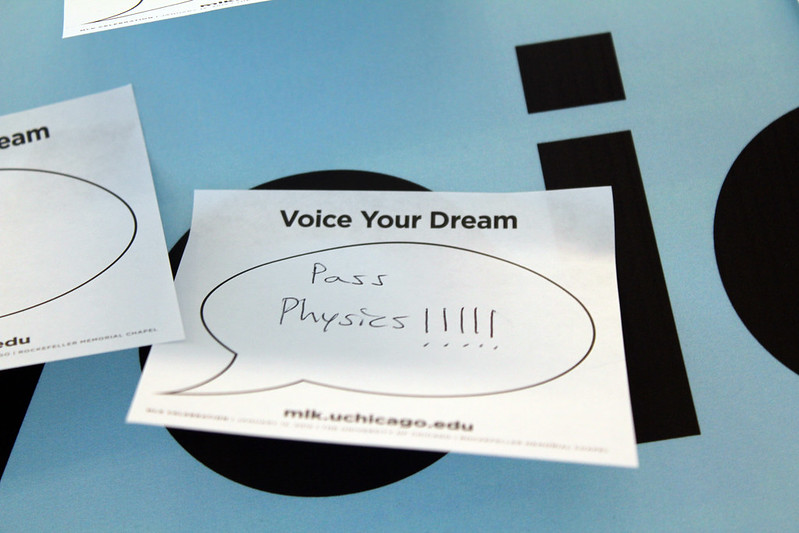

Being yourself is another huge message in the play. Felicia refused to allow being a colored woman in love with a white boy to limit her choices. Huey refused to change himself or sell out just to make it big in a world that couldn’t handle him anyway. One of the most important take-aways to Torres was “…the power of speaking your truth, to be who you are. I think the play really encourages folks to tell their story, to be creative and express their voice, and stand up against injustice.”

Isler had a more personal message, directed to the students of color right here on our campus. “Don’t lose your heritage. Don’t lose who you are just because you’re at NC State… Whatever you want to call yourself, colored, negro, black, afro American or African American…at the end of the day, I want you to look in the mirror and know who you are,” said Isler.

And after that, there is only this left to say. Memphis was an incredible journey. I laughed, I cried and I learned that even if love doesn’t always conquer all, soul will always survive. The show has thankfully been extended until September 11th, so get your tickets and experience the wonder, the sorrow and joy, the musical revolution that is Memphis.